Rapid City Health Center Designed to Enhance Community Connections

May 24, 2022 | Jennifer Seward

Located near the legendary Black Hills of South Dakota, the new Rapid City Health Center is designed to treat multigenerational members of the Cheyenne River Sioux, Oglala Sioux and Rosebud Sioux under one roof in a uniquely tribal health care concept.

The largest design-build effort to date for Indian Health Services (IHS), the center consolidates 10 existing clinic-based buildings into a 200,000-sq-ft, state-of-the-art medical facility, incorporating traditional healing, modern medicine and sustainable design features.

The Flintco/Scull joint venture team is partnering with Childers Architect, serving as architect of record, and HKS, which is serving as consulting architect and medical/interiors planner on the $120-million project. The partners bring a depth of experience to the project: Flintco has completed $2.8 billion in regional Native American projects and approximately $590 million of that has been with Childers.

“One specific challenge for the design team was to balance the Indian Health Services planning standards with the needs of the tribes. We tried to provide a modern health care facility that also supports traditional healing,” says Karl Kowalske, president of Seven Generations Architecture & Engineering.

A tribally owned firm, Seven Generations created the project’s bridging documents before handing them off to the Flintco/Scull design-build team to complete the design and construct the project. Upon completion, IHS will turn the building over to the three tribes to manage its operations.

In-house services include audiology, dental, eye care, primary care, podiatry and specialty care in addition to diagnostic imaging, laboratory, pharmacy, physical therapy, health education and a center for wellness and nutrition.

The health center is being built on land that was the home of the Rapid City Indian School in the late 19th century, a boarding school for Native American children removed from their families by the U.S. government. The school closed in the 1930s, and the site’s clinic building was constructed as a tuberculosis hospital for Native Americans, many of whom perished from the disease.

“There is an enormous richness to this project and story—balancing the gravity of the history while providing modern health care, modern medicine and sustainable design,” Kowalske says.

It was a complex project from every aspect, adds Seven Generations COO Jeremy Berg. When conceived, the project was the first multitribal health clinic for IHS. Seven Generations worked to build consensus among IHS and the multiple sovereign tribes, bringing them all together into one large-scale health center with bridging documents that took the project from initial concept through schematic design.

“We wanted to acknowledge what had happened on the site and make [this project] a way to move forward,” Berg says. “Every tribe is unique, and we looked for ways to organize the building that represented all of them.”

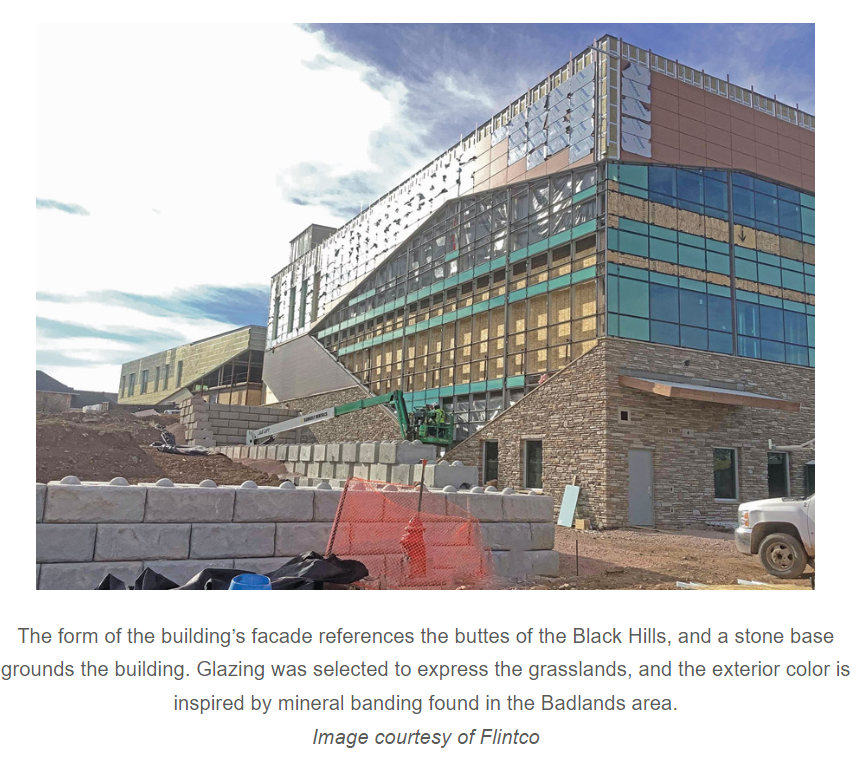

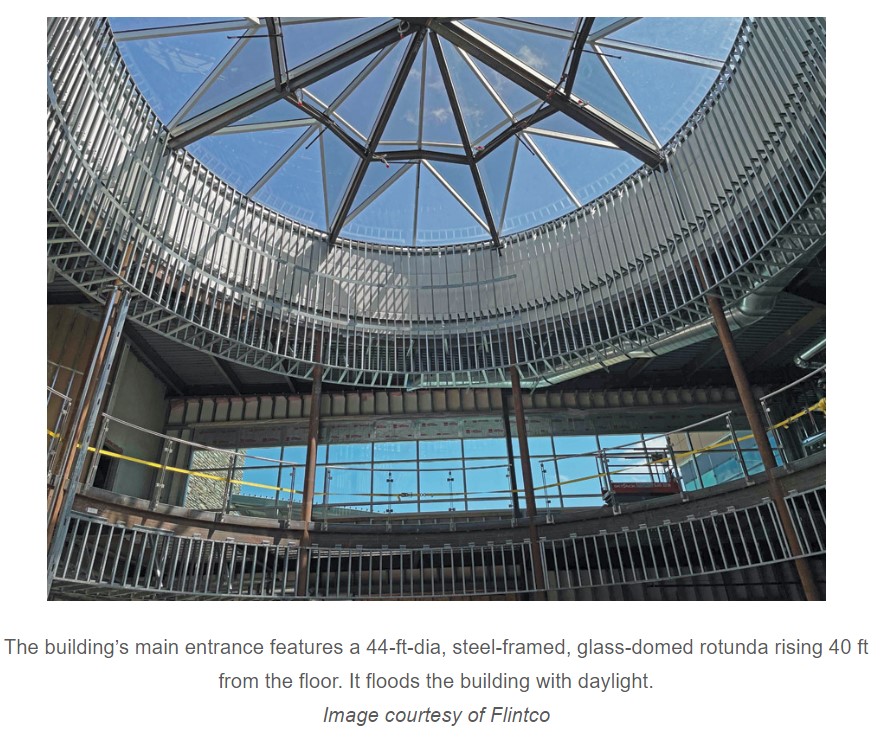

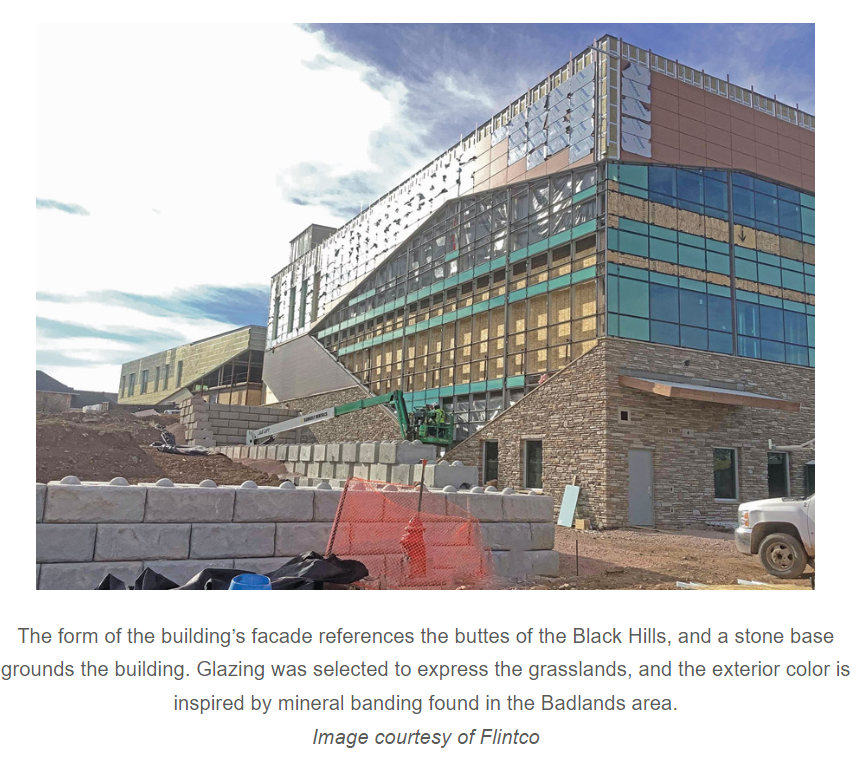

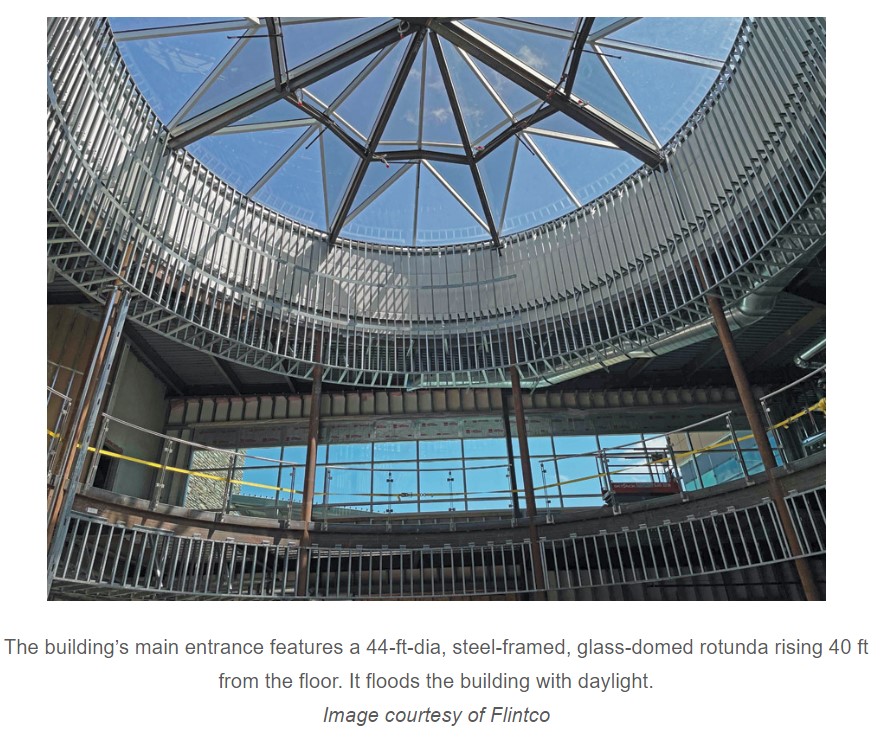

The design takes its cues from South Dakota geography: The eastern portion of the state is vast grasslands, the west has rocky cliffs and timberland and the Missouri River runs between them. The public entrance features a Lakota star skylight that floods the building with daylight to create a uniquely tribal space. From there, the main corridor, designed to mimic the river, divides the east and west portions of the building, which is further divided into four subregions that house different departments and feature colors, images and symbolism specific to each tribe. A healing garden is included in the outdoor landscape.

Based on a medical home model, the health center will serve as a one-stop shop for families coming together for various services and procedures. “The clinic is a place where tribal members will visit and stay for multiple hours. It’s a multigenerational experience,” says Steve VandenBussche, Seven Generations vice president of practice. “A grandmother might be coming with her granddaughter and have multiple appointments for each of them. Tribal members also travel hours to get health care, and once they’re here, providers try to give them as many services as they can.”

Complex Challenges

“It’s the type of project we enjoy in terms of coordination on an existing campus that had been in the making for several years,” says Flintco project manager Harry Knight. The campus encompasses approximately 40 acres, 30 of which were redeveloped to create the new health center. Flintco worked with Ferber Engineering Co., the civil engineer, to mastermind a phasing plan that ensured the existing facilities stayed open and operating while the new building was being built. “It’s a dance with all the pieces moving along together,” Knight says.

“The clinic is a place where tribal members will visit and stay for multiple hours. It’s a multi-generational experience.”

— Steve VandenBussche, VP of Practice, Seven Generations

The project broke ground in summer 2020, and crews worked to pour foundations during South Dakota’s harsh winter weather in temperatures that with the windchill felt like 30 to 40 degrees below zero. The building required completely new infrastructure—from power and water to sewer and fiber optics. Crews worked around the older buildings, navigating unforeseen site conditions like buried foundations from the old Sioux San campus that were not documented on the plans and dealing with cultural heritage issues that required they stop work to document buildings, provide historical records and protect archaeological artifacts.

“We encountered a system of underground concrete tunnels with steam pipe running through it. Asbestos materials in the 274 linear ft of pipe network had to be managed and abated. This was a cost driver that no one could have foreseen,” Knight says. “Those are the kind of things you want to avoid.”

Sustainable Design

Design guidelines for IHS projects require the building’s energy efficiency and performance be 30% better than the baseline energy model requirements. An underground cooling system creates ice during the night that is used to cool the building during the day. A stormwater system allows water to infiltrate into parking island bioswales and irrigate plants and trees.

Interior finishes feature materials with pre- and post-consumer recycled content, no volatile organic compounds, local sourcing and environmental and health product certifications. Indoor water-saving fixtures, a ground-mounted photovoltaic system and scheduled lighting controls also are key to the LEED Gold design.

State-of-the-art medical systems include a large imaging suite with CT, X-ray, MRI and ultrasound technology. “As the design-builder, it has been a privilege to sit down and interview each medical department to figure out what the equipment list should be,” Knight says.

“Other challenges came from the technical side; for instance, designing for a colder region where the freeze line is lower,” says Breck Childers, managing principal at Childers Architect.

A floor-to-ceiling light well in the rotunda challenged life safety and fire protection design, and with the onset of COVID-19, the team began rethinking “good” design, he says. “It was a balancing act from opened up and airy to the ability to close sliding glass doors around the reception desk to keep the spread of airborne viral agents down in case of another pandemic. We were continually balancing safety with the architectural aesthetics in place,” he says.

“Getting them into the facility is a huge health care driver for the tribes, which is much needed and long overdue.”

— Harry Knight, Project Manager, Flintco

With several entities involved, communication throughout the design phase was key. “Having the trade partners involved in the design process helped us issue a well-coordinated set of drawings,” says Childers project manager Mathew Thomas. “One challenge was to be sure we met exactly what was included in the bridging documents. There was a lot of back and forth to ensure everything in the bridging documents was covered while also ensuring we were code compliant and within the costs that Flintco had bid for the project.”

Knight adds: “The design-build model offers a better value to the client; you can design to their budget and target costs. [This project] was unusual in that they had very developed bridging documents. We did a lot of detailing for how it would come together, working with the materials in those bridging docs while also working within the client’s budget. It put the onus on Flintco to deliver a high-level, high-value project.”

Knight says Flintco will pursue this model with future projects when the client sees the benefits of design-build. “It has been rewarding to see it all come together—making what has been conceptualized manifest in reality. Getting them into the facility is a huge health care driver for the tribes, which is much needed and long overdue,” he says.